Turning the Pyramid on Its Head: America’s Long, Confusing Relationship With Food Guidelines

Written for Ravoke.com by Charles Mattocks Turning the Pyramid on Its Head For as long as I can remember, the food pyramid has been treated like some sacred nutrition roadmap

Written for Ravoke.com by Charles Mattocks

Turning the Pyramid on Its Head

For as long as I can remember, the food pyramid has been treated like some sacred nutrition roadmap — taped to classroom walls, printed in textbooks, and referenced by people who, in reality, weren’t actually eating that way anyway. So when news broke that there’s another new food pyramid, my first reaction wasn’t excitement. It was skepticism.

Not because clarity is a bad thing — we’ve needed that for decades — but because I’m not convinced the pyramid itself ever moved the needle for real people. I’ve yet to meet someone who stood in their kitchen, stared at a chart, and said, “Well, the pyramid says six servings of bread today, so here we go.”

Still, here we are again. Another reset. Another attempt to clean up confusion that arguably should’ve been obvious years ago. Processed foods? Not great. Added sugar? A problem. If that still feels like breaking news, then the issue isn’t the pyramid — it’s how disconnected our food system has become from common sense.

That said, the latest version does tell an interesting story, especially when you look at how we got here.

From Common Sense to Carbs on Every Plate

The Early Days: Before the Pyramid

Back in 1980, the U.S. government released the very first Dietary Guidelines for Americans. These weren’t flashy. No diagrams. No graphics. Just straightforward advice that looked like it belonged in a well-worn cookbook.

The message was simple: eat a wide variety of foods.

Fruits, vegetables, grains, dairy, meat, eggs, beans — nothing radical. The idea was that the human body needs roughly 40 essential nutrients, and no single food can deliver all of them. Milk, for example, brings protein, fat, calcium, and vitamins — but not much iron or vitamin C. The solution? Variety.

It wasn’t complicated, and it didn’t try to micromanage your plate.

1992: When the Pyramid Took Over

Twelve years later, everything changed.

In 1992, the U.S. unveiled its first official food pyramid, and suddenly nutrition had a hierarchy. At the base — the part you were supposed to eat the most — sat grains. Bread, cereal, rice, pasta. Six to eleven servings a day.

Above that? Fruits and vegetables. Then protein sources like meat, eggs, beans, and nuts. Dairy floated somewhere in the middle. Fats and sugars were pushed to the tiny tip at the top, treated almost like guilty afterthoughts.

On paper, it looked logical. In practice, it helped normalize a carb-heavy, ultra-processed diet that crowded out nutrient-dense foods. Six to eleven servings of bread doesn’t leave much room for vegetables, quality protein, or healthy fats — and nutrition experts now widely agree that recommendation missed the mark.

Even worse, the pyramid focused more on categories than quality. White bread counted the same as whole grains. Vegetable oil wasn’t distinguished from olive oil. Fat was fat, regardless of source.

The Pyramid Disappears — Briefly

By 2011, the USDA quietly retired the pyramid altogether. In its place came MyPlate, a dinner-plate graphic introduced during Michelle Obama’s tenure as First Lady.

It was simpler. Cleaner. Easier to understand.

But it didn’t last.

The Pyramid Returns — Upside Down

Fast forward to now.

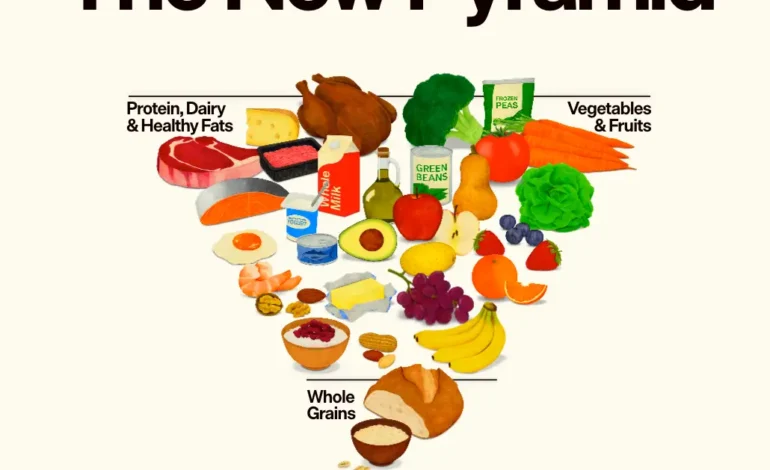

The Trump administration’s 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, released in January, brought the pyramid back from the dead — but flipped it completely on its head.

Literally.

This new version places foods you should eat more of at the top, and those you should limit at the bottom. And the message behind it is summed up in three words:

Eat real food.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. called it the most dramatic shift in federal nutrition policy in history, tying it to the broader “Make America Healthy Again” initiative.

Ultra-processed foods are out. Added sugars are under fire. Whole foods are back in the spotlight.

What’s Actually Different This Time?

Grains Take a Back Seat

Once the foundation of the American diet, grains are now minimized — sitting at the very bottom of the pyramid. No longer the star of the show, they’re something to be eaten intentionally, not endlessly.

Protein Finally Gets Its Due

Protein, which didn’t even have its own category until 2011, now plays a central role. Recommended intake has jumped from the long-standing 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight to 1.2–1.6 g/kg per day.

Plant-based proteins are encouraged, but animal protein isn’t banned — just no longer dominant.

Fat Isn’t the Enemy Anymore

Perhaps the biggest philosophical shift is fat.

For decades, Americans were told to fear it — especially saturated fat. Full-fat dairy was discouraged. Oils were suspect. Butter was basically contraband.

Now? The USDA says the “war on saturated fat” is over.

The new guidelines recommend full-fat dairy, healthy fats, and naturally occurring saturated fats from whole foods like avocados. Saturated fat is still capped at 10% of daily calories, but the tone has changed dramatically.

Sugar and Alcohol: Less Is More

Added sugar is now treated like the real villain, with a focus on strict limits — roughly 10 milligrams per meal.

Alcohol guidance has also shifted. Instead of setting daily drink limits, the message is simpler: minimize it. The old idea of “safe” amounts has quietly faded.

Pushback From the Nutrition World

Not everyone is celebrating.

Some experts argue that placing red meat and saturated fat near the top of the pyramid contradicts decades of research. Christopher Gardner of Stanford, who served on the advisory committee, has been vocal in his concerns, particularly about heart health.

Organizations like the American Heart Association continue to warn about excessive saturated fat, even as the new guidelines maintain the same 10% calorie cap.

And then there’s dairy — now elevated to the top tier — opening the door for full-fat milk and cheese in school meals. Emerging research suggests dairy isn’t the villain it was once made out to be, but the debate is far from settled.

Does Any of This Actually Change Behavior?

That’s the real question.

More than 70% of American adults are overweight or obese, largely due to diets built around ultra-processed foods and sedentary lifestyles. Whether flipping a graphic upside down will fix that is debatable.

But if nothing else, this new pyramid reflects a long-overdue admission: we got a lot of things wrong.

Maybe the future of health doesn’t live in charts or slogans — but in relearning how to eat like humans again.

FAQ

What is the new food pyramid?

The new food pyramid is an updated visual guide released alongside the 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. It emphasizes whole foods, protein, healthy fats, and reduced reliance on grains and ultra-processed foods.

Why was the food pyramid flipped upside down?

The inverted design shows which foods should be eaten more (top) versus less (bottom), reversing decades of carb-heavy guidance.

Is saturated fat now considered healthy?

Saturated fat is no longer treated as inherently harmful, but intake is still capped at 10% of daily calories and encouraged from whole-food sources.

What happened to MyPlate?

MyPlate has been retired, and the pyramid format has returned — albeit in a dramatically different form.

Does the new pyramid promote meat-heavy diets?

No. While animal protein is allowed, the guidelines still emphasize plant-based foods and discourage making meat the primary calorie source.